It was 2003. I was a first-year doctoral student attending my first research conference. I remember her as if it was yesterday. Except her findings. I was too consumed by the way she looked; her skin color, her tone, the way she looked at her students. At the end of her presentation I waited for my turn to speak to her – although I did not know what I wanted to say. All that came out was “Hi, I’m a student here. Thank you”, as tears ran down my face.

That image of a Latina scholar became engraved in my mind. When you see someone who looks like you, it gives you hope. I, too, could be there! I did not know it then, but that image – the way she looked and the way she acted – helped me when I wanted to quit or when I was in spaces that looked and sounded nothing like me. Spaces that invalidated my very existence.

“I am Dr. Silvia Lorena Mazzula. I am a first-generation college student, immigrant, and from a poor background. I was born in Uruguay and migrated to the U.S. at 9-years-old with my mother and younger sister. I am a mixed-race Latina. My great grandmother (a second-generation Uruguayan who died when I was 6) was the daughter of an African slave to an Italian family.”

This is how I usually begin the first day of my psychology courses or talks about creating cultures of equity and excellence in higher education.

As a child, I wanted to become a medical doctor. I didn’t know one, but that was the image of a professional I saw on TV: either a lawyer or a medical doctor (often male and light-skinned). I came from poverty. My first house had no running water- we collected water from a water well. My second home had no toilet, just a hole in the floor. At that time, my father was a factory worker and also a fisherman by hobby and necessity. My mother helped him sell fish on a makeshift table in the corner of a dirt road near our home. My parents separated after my father migrated to the U.S. My first job, at about 11 years old, was to help my mother and grandparents clean offices. They worked multiple jobs to make ends meet.

My parents did not graduate high school (though my mother earned her GED, and later an associate’s degree the year she turned 50). They did not drop out because they were not interested in school, but because they did not have the financial resources. My grandmother, now 87 years old, taught herself to read after being taken out of school in the second grade to work; that’s when she began cleaning houses.

My journey toward finding my calling in academia and as a researcher can be best described as one big roller coaster ride.

As is common for many students of color, I was coined an “at-risk” student and placed in remedial courses that did not prepare me for success in higher education (or life). I learned that I could go to college in my junior year in high-school. One vivid memory of that year is overhearing a peer rejoicing over her college acceptance letter. When I asked her about college, she jokingly told me not to worry because I would not get in.

Many people expected me to fail, to drop out of high school and become another “statistic”. My guidance counselor refused to give me four-year college applications. She said she was afraid of my reaction once I received the rejection letters. That message, that I would fail, gave me years of motivation to ‘prove that I belonged’: a journey that also included self-doubt, bouts of internal- and external-directed anger, and the impostor syndrome I still fight today, despite all evidence to suggest otherwise.

I went to The College of New Jersey, a predominantly White college, which was a culture shock since I come from a primarily Latino working-class community. Things as simple as seeing students walk around on campus in sweatpants or PJs were difficult for me to grasp. I found support in a Latina sorority made up mostly of first-generation college students committed to empowering their community through educational, social, cultural, and political awareness. We wanted to validate and support students like us in their academic journey. We also wanted our families to know what it was like – to see us in the Ivory Tower and know we were okay (they were not losing their daughters and we were not losing them nor our heritage). It was unusual then to have family members involved in college programs – from cooking the meals for our events to being active members of our audience. They were very much a part, and still are, of our academic life.

The experience of being a first-generation working-class Latina college student meant creating a home in a place that didn’t look like me.

I majored in biology. After I spent a summer in a pre-med program, I decided that becoming a medical doctor was not what I had imagined based on what I had seen on TV. However, I did not know questions that could have clarified that career for me. I also did not change majors as I saw many of my racial and ethnic minority peers encouraged to do. I wanted to prove to myself and others that I could make it. I did.

After college, I worked for a pharmaceutical company in a lab sampling water, at which point I came to another realization – lab work was not for me. I wanted to help others on a personal level, especially at-risk youth and first-generation college students with similar struggles. While I decided what I would do with my life, I worked selling yellow page ads and then as a waitress for a local diner. I felt lost.

Mr. Boatwright, then Director of the Educational Fund Opportunity Program where I had received my undergraduate degree, asked me if I would consider applying for a master’s program in counseling. I had never thought of going into psychology. Internally, I was resistant but reflected on my favorite high school teacher who taught psychology, Mr. Shiffman. I met him during a time when I was isolated and angry at the experiences of discrimination. Because I remembered him, I gave psychology a try.

As a master’s student, during a psychology externship program, I was struck that the issues discussed by many of my racial and ethnic minority clients (e.g., feeling isolated, culture shock, torn between college and family, acculturation stressors, and racism) could not be answered with the textbooks we had. Their life stories and histories were mostly missing from psychology’s understanding of human suffering and healing. Looking back, my calling was unfolding before my eyes. The last year of my master’s program, I met with my Department Chair, Dr. Mark Kiselica, who asked me if I had ever considered a PhD.

No, I had not. I did not even know what that meant.

What I began to realize was the importance of meaningful connections and to being mentored on an individual level. What I was unable to imagine, however, was that it was going to be a very lonely path.

My doctoral program, and later my introduction to the Ivory Tower as a tenure-track faculty member, mirrored my academic history. I continued to be, and continue to be, one of the only Latinas (at times the only racial/ethnic minority). I have had my abilities, and now credentials, questioned – I am rarely mistaken for the “professor” and more likely to be asked for instructions to the cafeteria. I’ve had students ask for the professor when I am in my own office, the only person in front of my computer – I just don’t “look like the professor”…. Must be my curly hair (which I now love but hated most of my life). I was una greñuda, which loosely translates to ‘a woman with disheveled/out of control hair.’ My hair excluded me from the rest, and it “needed to be tamed” – a message I received in 5th grade. By the principal. In class. In front of my peers.

But, I learned very quickly that I was not alone as I began to work on an invited book chapter on Latinas in leadership1 during my first year as a professor. While the topic deviated from my research on mental health, culture- and race-based experiences, it began to shape my purpose2. Learning the gross underrepresentation of Latinos in higher-education (e.g., ~7% of doctorates; ~4% of full-time instructional faculty across the country) and the day-to-day stressors they experience (e.g., discrimination, alienation, lack of institutional support 3-5) helped to shape my career aspirations to elevate Latinas in their academic and professional life.

As Latinas in higher education, we experience challenges, micro- and macroaggressions, that can eat away at our souls and the very drive we have as agents of change6. These experiences, mine and others documented in research and that occur more than they should behind closed and safe doors, are what inspired me to support Latina scholars, faculty members, researchers, and students in the pipeline through the Latina Researchers Network.

Building on the frameworks of racial-cultural psychology7 and Latina/o critical race theory8, I also started to reframe diversity, in my leadership, teaching, and research approach, into a position of healing that acknowledges the centrality of race (as a psychological phenomenon), immigration, language, and gender and one that challenges Western worldviews of pragmatism, objectivity, individuality, and future-orientation, so much infused in the fabric of the U.S. and higher education1,7-8. Together, these frameworks welcome and celebrate our racial-cultural value systems, “cultural resources” 9, and interconnectedness. A framework I believe can only be achieved through critical self-reflection and deliberate coming together of people with socially constructed power and those who have been marginalized.

Promoting relatable faces was nurtured by these frameworks, my research, worldview toward social justice, and experiences in academia – from childhood to those first years as a professor. For me, creating a culture of belonging is more than improving diversity and numerical representation. It is being transparent in my struggles, having an open-door policy, and sharing my knowledge10 to inspire and transform lives. It is elevating voices often silenced and honoring the shoulders of resilience we stand on.

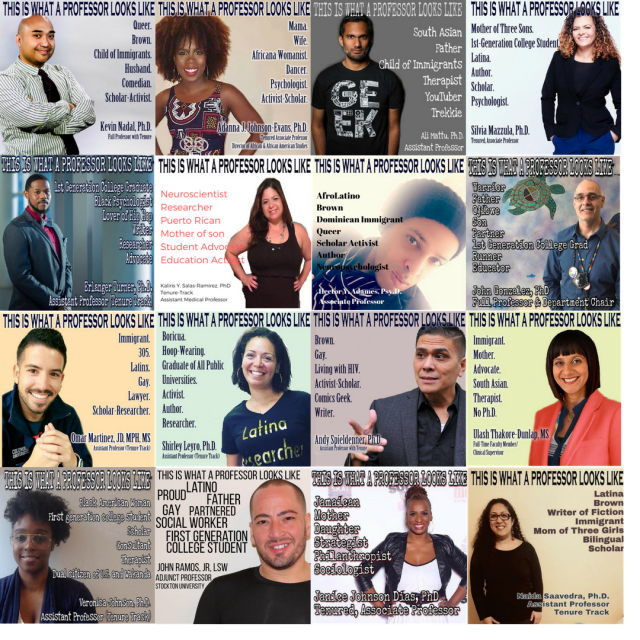

This was the motivation behind the Latina Researchers Network’s 2014 #LRNbeGreat campaign to elevate Latino/a/x professors. We leveraged social media to highlight the human story, cultural strengths, and lived experiences behind professors’ professional photos or degrees behind our names. We wanted students and colleagues to not only see themselves, but also know that our stories are what have made us who we are, that they are important and valid.

Engaging social media from a personal storytelling approach to show what a professor looks like, what a mother looks like, and what a Latina scholar looks like, did not only put me in a vulnerable position, and one with great responsibility, it was also a risky thing to do as a non-tenured professor.

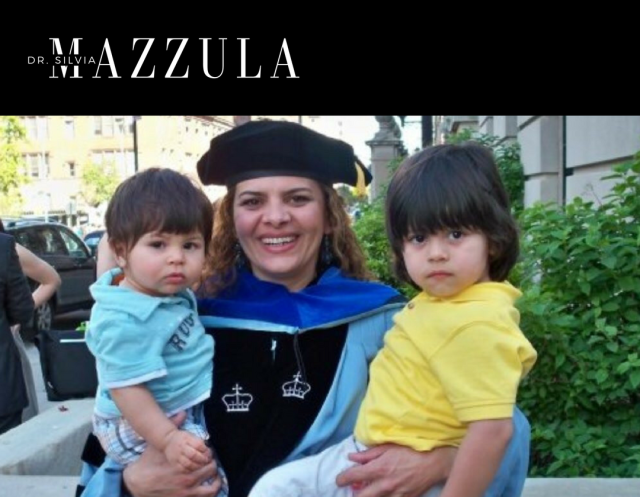

In 2015, others also began to work to change the image of what professors looked like through the hashtag #ILookLikeaProfessor. What was missing for me were Latinas/os/x and their stories. I added #ThisIsWhatAProfessorLookslike to the list of some of my favorite hashtags (#lrnbegreat, #imagesmatter, #workingmom) at that time with a post of me in my office, nursing my son. In essence, social media has allowed me to translate research for the public, but also to showcase the behind the scenes of being an academic: from challenges and microaggressions to embracing our authentic selves (and honoring all our roles). I am a mother, a wife, a sister, a daughter, granddaughter and aunt – I am my family and my community. I graduated from Columbia University with a 13-month-old and a 3-year-old. I had my third son while applying for tenure and promotion. Latinas and mothers, for example, need to know they are valuable. We don’t all look like Google’s image of “Professor”.

Dr. Mazzula with her sons at her PhD graduation from Columbia University in 2009

I am a social justice scholar and this is infused in my classrooms, research, and leadership. However, I would have never imagined then, that my participation in social media, in this very personal and culturally congruent way, would inspire and empower so many.

More recently, my colleague Dr. Kevin Nadal and I decided to further promote #ThisIsWhatAProfessorLooksLike by showcasing historically under-represented racial and ethnic minority professors through uniformed memes.

To be an educator is to be in the pursuit of moments that inspire.

Vulnerability and visibility help me empower those who need to “see” themselves and elevate the relatable faces that were missing for me. I am now a tenured Associate Professor of psychology. I am intentional in sharing my roller coaster ride into higher education including the lack of equitable policies and programs that do not include, and often exclude, Latinas/os/x, but also the cultural, racial, gendered, and familial strengths that help us survive the academy. There is a myth that success means having all the answers, that we must have a clear “dream” of our future, and that it is a linear path. However, many people from under-served communities (women, first generation students, those from poor backgrounds, etc.) may not have an image of what that looks like in the first place. While I was lucky to have a Mr. Shiffman, Mr. B., and Dr. Kiselica, most of my encounters with professionals throughout my life were not as positive. There is real pain in our academic journey, one that begins when we are young.

Images, relatable faces, and personal narratives matter. This is one way we can nurture and validate the mind, body, and soul of those who have, and continue to be, marginalized. If we all join in elevating diverse faculty members, our students will be more likely to see themselves reflected in higher education. After almost 8 years on social media as a professor and scholar, I can guarantee you there is someone out there right now that is waiting to see someone just like you to inspire them to fulfill their life’s purpose11.

Join us. Follow #ThisIsWhatAProfessorLooksLike on Twitter and on Instagram

#ThisisWhataProfessorLooksLike memes, half of which appeared in “This is What a Professor Looks Like” by Dr. Kevin Nadal.

Author Note: Thank you to my colleagues and friends, Dr. Pamela LiVecchi, Dr. Lisa Aponte-Soto, and Mr. John Ramos Jr. for the invaluable feedback and support in the revisions of this blog.

References:

- Mazzula, S. L. (2011). Latinas and leadership in a changing cultural context. In M. Paludi & B. Coates (Eds), Women as Transformational Leaders: From Grassroots to Global Interests (Vol. 1, pp. 143-169). Praeger Publishers.

- Mazzula, S. L. & Quitos, A. (2010). Why are there so few of us? A roundtable discussion on Latina leadership. (Roundtable). National Latino/a Psychological Association Biennial Conference, San Antonio, TX.

- Gutierrez, G., Muhs, G., Niemann, Y. F., Gonzalez, C. G., & Harris, A. P. (Eds.). (2012). Presumed incompetent: The intersections of race and class for women in academia. Boulder, CO: Utah State University Press.

- Delgado-Romero, E. A., Flores, L., Gloria, A., Arredondo, P., & Castellanos, J. (2003). Developmental career challenges for Latino and Latina psychology faculty. In L. Jones & J. Castellanos (Eds.), The majority in the minority: Retaining Latina/o faculty, administrators, and students in the 21st century (pp. 257-283). Sterling, VA: Stylus Books.

- Zambrana, R. E., Ray, R., Espino, M. M., Castro, C., Cohen, B. D., & Eliason, J. (2015). ‘‘Don’t Leave Us Behind’’: The Importance of Mentoring for Underrepresented Minority Faculty. American Educational Research Journal, 52 (1), 40–72. DOI: 10.3102/0002831214563063

- Mazzula, S. L. (2017). Social capital, community and access: Lessons toward workforce diversity. American Evaluation Association: AEA365 A Tip-a-Day by and for Evaluators. American Evaluation Association. Retrieve from http://aea365.org/blog/social-capital-community-and-access-lessons-toward-workforce-diversity-by-silvia-mazzula

- Carter, R. T. (2005) (Ed.). Handbook of racial-cultural psychology and counseling: Training and practice. New York, NY: Wiley.

- Solorzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2001). Critical race and LatCrit theory and method: Counter-storytelling. International journal of qualitative studies in education, 14(4), 471-495.

- Delgado Bernal, D. & Villalpando, O. (2002). An Apartheid of Knowledge in Academia: The Struggle Over the “Legitimate” Knowledge of Faculty of Color, Equity & Excellence in Education, 35(2), 169-180.

- Rangel, R. & Mazzula, S.L. (Winter 2013-2014). Mentoring Latinas. Newsletter of Section 3- Concerns of Hispanic Women/Latinas. Division 35: Psychology of Women (Issue 2). American Psychological Association.

- Mazzula, S. L. (November 2017). Technology and social justice: Healing Wounds (Keynote). Making Achievement Continuous Annual Conference. The College of New Jersey, Trenton, NJ.

Related links:

- Chi Upsilon Sigma – National Latin Sorority

- Latina Researchers Network

- #LRNbeGreat

- #ILookLikeAProfessor

- “Professor”

- #ThisIsWhatAProfessorLooksLike Campaign

- Uniform memes

- #ThisIsWhatAProfessorLooksLike on Twitter

- #ThisIsWhatAProfessorLooksLike on Instagram